Rae Joyce got in touch to tell us that she shared our fascination with Mary Taylor, the radical classmate who pushed Charlotte Brontë to earn her living by the pen. We were keen to learn more – not least since, like Taylor, Joyce is a Yorkshire woman living in New Zealand.

I drew Mary Taylor – in truth, she drew me to her.

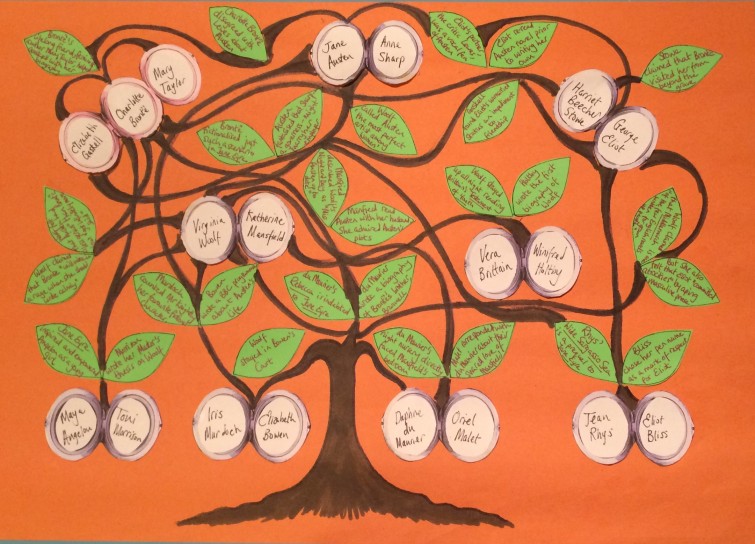

In early 2016, I was sitting at the kitchen table with my partner batting around ideas for a project in which I could reconcile both of my hemispheres: Yorkshire and Aotearoa. As an English woman in New Zealand, I occupy a position of privilege that doesn’t sit comfortably with my working-class roots. I had always considered myself an underdog in the UK. But I’d recently finished co-editing Three Words, An Anthology of Aotearoa Women’s Comics (Beatnik), a book that sought to redress the erasure of women’s comics history in New Zealand, which forced me to acknowledge the link between comics and colonialism in Aotearoa. The book, and my essay included in it, was something of a stick to the wasps’ nest of the dominant culture of New Zealand comics. My partner, Māori poet Robert Sullivan, a former librarian, knew better than most what I was trying to achieve when he said, “Didn’t Charlotte Brontë have a friend who lived in New Zealand?”

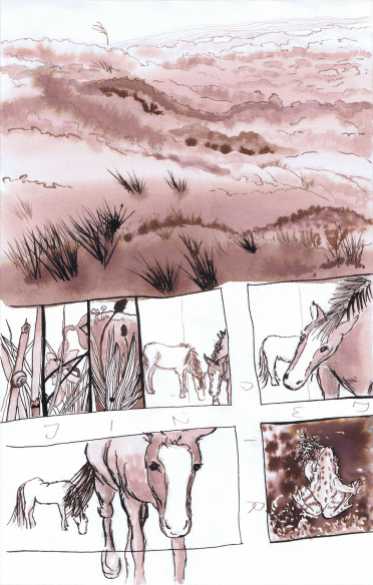

I had read Jane Eyre in my teens and still had my copy. I put it in the laundry room where I had a small school desk and opened my laptop. Although I had a copy of Shirley, I hadn’t read it, so hadn’t yet encountered Rose and her family whose depictions Charlotte drew from Taylor and her family. But as I accumulated Brontë biographies and articles, an outline emerged of a woman I felt a strong pull to make out. Only one academic biography of Taylor had been published, and while I waited for a copy to arrive in the post, I began to draw.

For as long as I can remember, as well as writing, I have drawn and painted. I grew up in a small South Yorkshire mining town, until I didn’t. Which is to say, when the pits were closed, the pit head gear demolished and slag heaps overplanted the way kids scribble to hide their mistakes, I grew up on the edge of a ground-down town, cut off from all but a few houses by the new by-pass road that meant nobody had to drive through the place. At night, I would look out over the whips of birch at the brown-orange haze of streetlights above and the terraces silhouetted against them and wonder why the terrace I lived in was all on its own. Stories were my imaginative escape in lieu of the real thing.

It was a shift in circumstances that drove Taylor to Te Whanganui-a-Tara, as Wellington was known to Māori before Pākehā/Europeans arrived. After the death of her father, the family woollen mill passed to her eldest brother, and with it, her home. Taylor’s father had taught her never to marry for money, encouraging her in the belief that would underpin her writing: women must work. She differed from her best friend Charlotte in that she did not pay heed to social mores that considered work for women to be degrading – she referred to the working-classes as an example for the equality that could exist between the sexes. And by working and living independent of men, Taylor lived by her words. She set sail alone. But she maintained her friendship by letter.

Like Taylor, I travelled to New Zealand to improve my circumstances and to write. I have lived in Auckland almost as long as Taylor lived in Wellington, during which time I have corresponded with my best friend via letter. When my research for Taylor’s biography took me to New York in February 2017, I met my own Brontë in person for the first time.

Unlike the real Charlotte Brontë, Loredana Tiron-Pandit migrated, from Romania to Massachusetts. She is no coward. She is also the best supporter and encouragement a woman could have, and she never baulks from telling me what she thinks (Taylor would have loved her). She also helped me draft the copy of my graphic biography with text boxes that resemble torn fragments of Taylor and Brontë’s letters, because she is brilliant at all things ‘computer’ and I am a Luddite. (Taylor had a lot of sympathy for the Luddites. What an amiable bunch we four lasses would have made!).

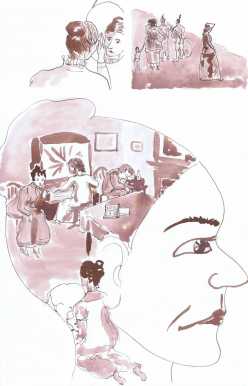

As I pored over Taylor’s correspondence with Brontë I could not help but reflect on the letters – proper old fashioned paper letters – I had shared with Lori, how she was my first reader; how much I valued her honest opinion; how much I had come to rely on her and looked forward to her letters the way Taylor did – my driveway is no Mount Victoria, but I climb it with no less enthusiasm to check the mail box! My friendship with Lori was my first port of call for answering my questions of ‘How would Mary feel?’ Always at a distance, always waiting for a reply. And the satisfaction of handling the paper and reading the words in my friend’s own hand – Lori was never far from my thoughts as I shaped my book.

And this is how my thoughts ran throughout the whole process of researching and drawing then inking the book; it wasn’t me finding out about Taylor, it was me and Lori talking to Charlotte and Mary. Sometimes I confused us. Sometimes I wanted to shake Taylor for her part in colonising Aotearoa. And once, in the Brontë Parsonage Library, I called Brontë a bitch. Taylor found the process messed with her head. Concerned for her health, she wrote to Brontë afraid she would slip into a state of “betweenity”. Body in New Zealand, head in Yorkshire.

I empathised.

Writing as Rae Joyce, Rachel J Fenton co-edited Three Words, An Anthology of Aotearoa Women’s Comics(Beatnik, 2016) and her participation in the NZ Book Council Graphic Novelist Exchange Residency in Association with the Publishers Association of NZ and the Taipei International Book Exhibition resulted in Island to Island, a Graphic Exchange between Taiwan and New Zealand(Dala/Upstart Press). Winner of the Auckland University of Technology Graphic Fiction Prize, Rachel is currently looking for a publisher for her graphic biography of Mary Taylor, Charlotte Brontë’s best friend, which she researched and drew with arts grant funding from Creative New Zealand.

Edited by Clêr Lewis.Clêr has an MA in creative writing from Goldsmiths, University of London, and is working on her first novel.

If you too have an idea for a future Something Rhymed post, please do get in touch. You can find out more about what we are looking for here.