Half a year of social distancing has lent us a new perspective on our writing, our friendship and the future of both…

Emily and I enjoyed an alfresco Vietnamese lunch recently – the first time we’d seen each other in person for over six months. Even during those periods when we lived in different countries or continents, we’d never let more time lapse between meetings than this.

Back in December 2019, Jonathan and I moved to a new house, closer to Emily and her family. Early in the new year, Emily came over to this new house, and here we workshopped a draft of her new book, and later had dinner with another writer friend. Not long afterwards, I babysat eight-month-old Lola so that Emily and Jack could go out for dinner on their wedding anniversary.

On each occasion, we marvelled at the newfound ease of train travel between our homes, and we were looking forward to spending even more time together. Never could we have predicted that the short distance between us would become so difficult to bridge.

When we did eventually manage to meet again, we talked for hours over bowls of pho and duck curry, and it felt almost possible to forget the pandemic. But socially distancing across our outdoor dining table was a far cry from the desks behind which we so frequently squeezed as we looked at the same age-faded letter or shared the same screen while working on A Secret Sisterhood.

Much as we both miss those days when we occupied ‘a room of one’s own to share’, as we once called it, the past months of enforced separation have also given us the space to look at our writing lives with a new sense of perspective.

We’ve come to appreciate just how much our joint work on female literary friendship has shaped the separate projects that engage each of us now.

Emily will soon be turning in the final edits of her new non-fiction book, Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice, which will come out in May 2021. She caught a first glimpse of this transatlantic network of female spiritualists when reading unpublished letters from Harriet Beecher Stowe to George Eliot for A Secret Sisterhood.

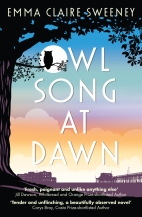

Similarly, my new novel took shape as I researched the life of Virginia Woolf. And my longstanding belief in the value of mentoring has only been reinforced by the number of writers we’ve featured here who have benefited from such arrangements: Elizabeth Bishop and Marianne Moore, for instance, Katherine Anne Porter and Eudora Welty, Zora Neale Hurston and Dorothy West.

Much as our current literary ventures may have sprung from the same source, they are taking us in new directions, separately and together, as writers and as friends. And so, during these months of sequestering ourselves away in our individual studies, we’ve immersed ourselves too in different psychological spaces.

Something still rhymes, of course: between the writer friends featured on this site; between its community of editors, contributors and readers; between Emily and me. But during that meal we shared, between sips of green tea, we agreed that we needed to give this new stage of our writing lives greater space to grow. Just as important, we both want to nurture this next phase of our friendship – and we want to do this offline. And, so, after much consideration and with not a little regret, we have decided to bid this site farewell.

As we say goodbye, we’ll leave you with the words of Jane Austen – one of the first authors we featured on Something Rhymed:

“But remember that the pain of parting from friends will be felt by everybody at times, whatever be their education or state. Know your own happiness. You want nothing but patience; or give it a more fascinating name: call it hope.”

We’d like to take this opportunity to thank all the writers who have contributed to Something Rhymed, all its readers who’ve created such a vibrant community, and, especially to our editors Kathleen Dixon Donnelly and Clêr Lewis, without whom we could not have kept Something Rhymed going for so long. You can join Kathleen’s own literary community over on her site, Such Friends. And do watch out for Clêr’s first novel All the Captured Shadows, which she is in the midst of drafting.

We’ll be keeping this site online to maintain an archive of female literary friendship, and you’ll still be able to post comments.

Do keep in touch. You’ll still find Emily on Twitter, Instagram and her writing website, and Emma is on Twitter, Facebook and has her own website too.