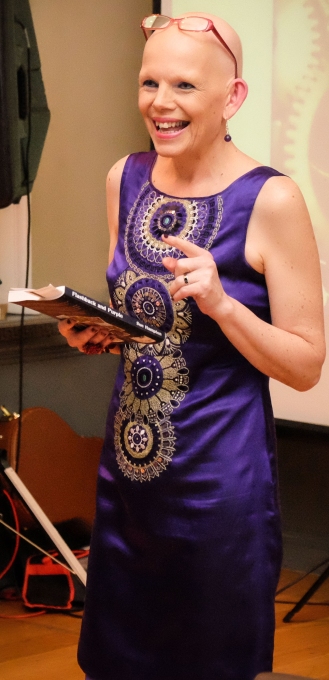

We were delighted when Sue Hampton, a former teacher who has written many books for children, offered to pick up on a point raised by several of our speakers: the gender divide starts young.

Having taught for nineteen years before I became an author, and subsequently visited 600 schools, I’m familiar with several statistics about gender issues in children’s books and literacy. Firstly, the majority of teachers are women (87% in primary, 62% secondary). Secondly, according to the National Literacy Trust, girls achieve better reading test results, enjoy reading more and spend more time on books, all of which impacts on writing standards. Thirdly, 15 out of 18 titles shortlisted in the Waterstone’s Children’s Book Prize 2015 were written by women and some of the bestselling novels for young readers in recent years were by J.K. Rowling, Stephanie Meyer and Suzanne Collins.

In my career as a primary school teacher I was made aware of the drive to close the achievement gap with reading and writing tasks targeting boys. Eight years later I find that when I’m asked to work as an author with more able writers, these groups are predominantly female and beyond Y5, often overwhelmingly so. If we are looking for gender equality in children’s fiction, reading and writing, the evidence might suggest that it’s boys (and possibly male authors) who are at a disadvantage. I must also point out that Michael Morpurgo has created some of the strongest female characters I’ve encountered on the page. However, I would argue that if we look wider and deeper, while everything for girl readers may be pink, the picture is far from rosy.

In society today we see a gender divide across clothing, shoes, toys and books that presents girls as pretty princesses until they grow into teens who love boys and shoes, and boys as technically-minded fans of war and football. It’s a divide that limits everyone, generating characters as stereotypes and marginalising, or at least unsettling, the girl who is too independent-minded or physical for the market – along with the emotionally literate boy. I met a teacher who thought she had secured a writing future until her prospective agent told her she would have to change her strong, adventurous female protagonist to a boy – and this pink-blue divide, presumably as much a sales ploy as a well-intentioned outstretched hand to draw boys in, inevitably shapes attitudes and expectations around identity. This may explain why, when I ask classes Y5 – 7 to create a character to follow the powerful male baddie who begins my book The Dreamer, at least 70% of the boys imagine an avenging hero who will conquer him, and almost all the girls foresee a female who will redeem him with some kind of love.

Yes, there are exceptions. Yes, The Hunger Games, like the movie Brave, has a female action hero. But I’d argue that strength doesn’t have to fulfil traditional male criteria of competition and domination, and that peace and justice may be better served if children’s fiction celebrates alternative kinds of courage and power. I believe one solution to the self-fulfilling prophecies of blue and pink fiction lies in stories embracing diversity and individuality regardless of gender. It’s my intention to create boy and girl characters, whole and complex, who are uniquely and honestly themselves – just as we would like our children to grow up to be.

Sue Hampton’s latest book for adults is Flashback & Purple.

Please do share any of your ideas about how to avoid such gender stereotyping by using the comment facility below.